Beginnings

December, 2021.

There’s an idea that I’ve had for some time…

In 2020, I found myself largely confined to a tin can apartment in the sky, Somewhere in the South of Singapore. A particularly unhappy time in my life, as it was for everyone else really, I found my only outlet for if not normality then at least comfort came in the hour or two I would have of an evening when I would retreat to the rooftop overlooking the city below me. To the north and west, a shroud of permahaze that had lifted due to the lack of everyday human activity, revealed the tabletop mountains of Malaysia that framed each nightly twilight. To the south and east, across the Strait of Malacca, lay the regional cities of Indonesia, their lights twinkling across the sea, providing the reminder, as if it could ever be forgotten, that I was trapped on an island, far from home and away from all those closest to my heart. In this solitude, I went through the heartache of a breakup, worked through a manner of gaslighting and a matter of what should have been a kind of pressure and a set of expectations beyond all levels of rationality, and lost two years of my life. From this perch aloft a tropical paradise turned prison, enduring the worst moment in the country’s history since the occupation by Japan and its abandonment by Britain during the Second World War, my escape came in firstly thinking about and finally committing to the task of getting that idea down onto paper.

At some point during that year and more that doesn’t count, in the evenings, I clambered, fountain pen and hard leather backed Moleskine in hand, to a spot amidst the clouds with the simple goal of writing just one page of notes for each Classic story.

Initially, I scoped out the structure and content of each Doctor’s era, pruning and reordering stories into a sequence and shape. I wanted to preserve the feel and even mystique of each era, attempting to be faithful by keeping what at their hearts comprise the boiled-down bones around which everything else is built. Some things were lost, a few things were reshaped, but many things stayed in place and true to their form, always in essence if not always in every aspect.

This blog represents the first pass through of some 135 stories that would comprise a reimagined version of Classic Doctor Who – the results of 135 nights, some easier than others, others harder than most, but each different. And different because every night was a different adventure. Each evening was a chance to relive sunlit memories of Target adventures of my middle childhood or of the television-lit late night video marathons of late adolescence, re-engaging with a text I thought I knew so well but that was revealed again to me through a new set of prisms that were created over a lifetime of loving this silly little show that somehow, somehow became so much more important than just that.

At some point in early 2021, I reached the end of my initial pass-through. I began to transcribe my handwritten notes into my MacBook as Singapore began to open up. Sitting in a favourite café on Duxton Road in the downtown neighbourhood of Tanjong Pagar on Sunday afternoons, I began to further flesh out each entry.

New and better ideas and takes came to me on each revisit. Tens of thousands of words later, I had what I considered to be the foundation for what could become a blog. But still I was unable to leave this island, still I wasn’t able to travel to see my family and friends. Worse still was that I did not know exactly when I would see them all again. So as a way to make the most of the time between the then and the now, I committed to another milestone that I knew had to be done for me to consider this creative fool’s errand to be ready for reading by anyone else at all: I realised I would need to have a breakdown for each story. Each entry in this blog will have a summary as well as a synopsis. In committing to that, I realised I would blow out the size of this project to something that would run to hundreds of thousands of words, and from months to years if not beyond. I figured that, if I was going to go tilting at windmills, they may we as well be the biggest and most beautiful windmills that I could conceive of.

So if those are the personal reasons as to why am I doing this, what are the what could come close to some of the articulatable, defensible creative imperatives that would compel me to even think about committing to such a useless endeavour, never mind in the process to betray an actual temerity to rewrite an entire series, as though I could do any better and not much, much worse?

You see, rattling around in the back of my mind, day and night for years and years and well before the terrible business of the last few years, has been this question of what would Doctor Who look like if it went mainstream, big budget, and across to a Netflix, Disney, or Amazon – basically, what if it became the next Game of Thrones? Let’s face it; it deserves to be, it has the potential for it, and at some point it probably will happen. There is not only a rich mythos to Doctor Who, but moreover a completely unkillable format that would both capture the imagination of an audience and lend itself to the televisual landscape of the early C21st.

The success of the likes of Harry Potter, GoT and the Marvel films shows that people are drawn towards – even have a hunger for – a kind of escapism that is at the same time made believable through told human stories that are visually convincing; our make-believe needs to be beautiful and realistic. At its best, this is exactly what Doctor Who does, particularly since its return in 2005 but also, in glimpses and at times, throughout its entire run dating back to 1963. So what would you need to do to bring our favourite show to a truly global audience and appreciation? The basic working premise of this entire, fanciful, even crazy project is that, to do this, all you need to do is to take the frame of the whole of Doctor Who and re-fit it all out, keeping its pure hearts while reinvigorating its whole body.

And all I could conclude, in all honesty if not stupidity, was that you would need to do this by starting at the very beginning with An Unearthly Child and going all the way through, up to and including the present day…

I know, I know. I can already hear the voice of the fans (and also my own inner fan): “You can’t do that!”, “You can’t just rewrite the history of an entire program!” “You can’t rewrite canon!”. With all due respect; yes, you can – and you wouldn’t be alone in doing so while bringing an old story to a new audience. In fact, there are two really strong examples that we need to look at, both ancient and modern, to prove that you can.

The retelling of stories is how we have received the Greek myths – and why still have them. Do you know which bit in Iliad by Homer tells the story of the Trojan Horse? None of it. There is only a passing reference that comes to just four lines in Book XIII but it doesn’t actually depict the story in any detail at all. So one of the oldest stories of Western antiquity comes to us not through a ‘canon’ of books or ‘authorised versions’ – no such thing actually exists for what is known as the Epic Cycle that comprises all of the Greek myths – but through a tradition of oral storytelling that we think was probably been written down by a variety of scholars over a period of centuries, but that pretty much all of which was certainly lost even centuries before the time of Christ. Nobody can even agree on who the Heroes in the Horse were! No: With a story so central and famous to the western literary tradition as the Trojan Horse, there is no canon.

So how does this story survive if it is outside of a codified, consistent, written form where people can agree that this is the ‘one true and real’ version of events (a series of events, we should be clear, that never actually happened)? How do we know the story of the Trojan Horse if it isn’t ‘in the canon’? The answer is that it there isn’t one true version and never has been, and that it exists only due to the fact that it is such a compelling, stirring, and iconic story that was told – and, more importantly, retold – over and again down the centuries until it became a part of our inherited and shared culture because it said something about our own experience that we wanted to keep and knew would be make us so much poorer without it, and because we never wanted to let it be forgotten.

So the story survived because people kept retelling it.

We can’t help ourselves. It is that good – we keep telling and retelling the same story! And we all know what happens to a story when you retell it over and again; it changes, it adapts to suit the audience you’re telling it to, it morphs into different versions, where one person recalls it one particular way, and another has another version of it. Now multiply that by the number of generations over some five thousand years, in hundreds of languages, and reaching millions of people, and you’ll realise that there can be no such thing as canon when it comes to the Trojan Horse.

But a five thousand year old story is not the same as a fifty year old television programme that is probably the most documented show of all time, you correctly say, and I agree with you on that count. But we have a more rwecent example that offers a perspective that it isn’t just the old, barely literate story-telling habits of the many worlds from long ago that results in there not being a canon: The comic book. Over a period of less than a century, how many versions of Superman or Batman have we had, and –just as importantly – why isn’t there a refusal by even a single fan to accept anything other than the original Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster or Bob Kane stories from the 1930s? Why is there no one, single, unified canon in the comic books? Because the telling of the story – told by subsequent generations of writers and directors – that is being told now (whenever now might be) is the most important factor, and something only ‘counts’ as ‘canon’ when it has a use in the story being told; ‘canon’ is only important in so far as it has a narrative purpose. In the comics, there technically isn’t a ‘one and true’ version of events – or a canon. And everyone seems to be pretty happy with this.

It’s an interesting question to ask why, though – like the notion of ‘canon’ – I actually don’t think there is one, definitive answer. But the one I like best is that the wide-eyed child sitting in front of the silver screen watching Avengers: Endgame in 2019 and the kid reading a Wolverine comic in the 1980s and the boy who picked up that first issue of Action Comics #1 in the summer of 1938 all need and expect different things from their stories and versions of the myth that they are about to experience. Audience expectations change to reflect their context, and you can’t expect the trappings and conventions of the way that a particular story tells events that, remember, never actually happened to be exactly the same across the years, decades, or even millennia. But if you take the myth and boil it down, you will still have most of its bare and basic bones, and that is all that you can – and should – use as your starting point when telling the story again for a new generation or another audience to not just hear of it, but to love it as their own.

(On a side note that is nonetheless fundamentally crucial to understanding one of the key motivating forces of this project, it’s important to note that, in so doing, comic books tread the same path as the Greek myths; that is, they become not simply stories in themselves, but part of a mythos. I make no apology for my belief that Doctor Who is itself a mythos: It is the perfected form that television has developed, using its own evolving language and very medium, to tell the one myth that humanity keeps telling itselv over and again, harnessing the strong archetype of the Stranger and the Hero’s Journey narrative (much more of which to come in time and later. Like the Heroes of the Greek myths and the icons of the comics that continue to resonate to this day, Doctor Who is constituted of the kind storytelling that will mean that it will, ultimately, outlive us all.)

To put a line under my argument, let me just offer just one more piece of evidence through a question and its answer: Does every bit of even televised Doctor Who fit seamlessly into one continuity or ‘canon’? No, obviously, and the reason for that is the reason that will keep Doctor Who alive forever – Doctor Who was never written, performed, and produced as a single piece of work by any one person alone, and change is in its very DNA.

Like the myth of the Greeks or the comics, Doctor Who is a populist, egalitarian, enfranchising, and ever-unfolding text inherited by an increasingly larger and more varied audience, and that – in return – the mythos becomes richer for the multiplicities of its tellings and retellings. And, maybe stupidly, my ambition and aim is to prove to myself as much as anyone else that Doctor Who is the greatest mythos, never mind television show, of the televisual age – and so, after a lot of labour, love, and loss – here is a telling of a re-imagined Doctor Who.

It is Monday, 20 December 2021. It has been twelve days since my third vaccination shot, and with that, I am able at last to be sitting in the departure lounge of Changi Airport. I write this waiting for my plane to bring me home to see my parents and siblings. Two years have disappeared. And all I have to show for it are these idle reimaginings. I hope that you enjoy them even half as much as they were a kind of consolation to me in the time in between the then and now.

In media res (An update)

January, 2023.

Writing detailed breakdowns of how I would rewrite classic Doctor Who stories isn’t easy – or at the very least it is time-consuming.

It’s been a year since I got back from Sydney where I was able to see my family and friends again. In that time, I have been back to Australia – under the least ideal circumstances – but have also been able to get back to Europe and see my friends in Italy, the Czech Republic, and the UK. I am lucky to have such wonderful and supportive friends across the world, most of them fellow Doctor Who fans, and – to my surprise – when I told them what I got up to isolated during those difficult years, they were supportive, interested, and even intrigued. I want to thank them here for their kindness and friendship. So thank you, Erik Stadnik, Joe Ford, and Colin Sillitto – three people whose opinion on Doctor Who I value and three people whose friendship matters to me more than they could possibly fathom.

Also in that time, I have also been chipping away at the synopses for the 15 stories that form the era of the First Doctor in my reimagining. At about five thousand words each, I’ve written in that time about the same number of words that I did during those two years. Each Doctor will have about 80,000 words dedicated to their reimagined series. I figure I now have about a year’s worth of publishable content, which is about as narrow a buffer as I would be comfortable in having up my sleeve before I start publishing anything. You’re reading this just as I finalise the website on which you will read this and just as I begin my journey through the Second Doctor’s era. (I’ve been saving the animated version of “Power of the Daleks” for just this occasion, and you can imagine my delight to have learned that they have since released a reanimated version!)

It is the morning of Monday, 23 January. The sun is rising on another warm morning in a very different Singapore to the one in which all this began almost three years ago. Today is the first of the Chinese New Year public holiday. It’s also the day that this site goes live. I figure it’s an apt a time as any. And for the first time in a very long time, I’m looking forward to what is yet to come, whatever that may be. And I’d love for you to be a part of that – welcome aboard!

How it all works

Before we actually do start, let’s have a look at how this will all work. The page for each Doctor will include the following information:

The Nth Doctor

When we come to a new incarnation of the Doctor, we’ll stop and have a chat about the direction of the arc of this character; what the intent will be in terms of the development and how that will play out in the form an arc. New Who audiences are going to be more likely to accept this kind of thing, but many Classic Who fans will at least accept, if not identify and maybe adore, the way in which each incarnation of the Doctor evolves and progresses towards a recognisable state until, finally, we say our goodbyes to each of them in turn. This will be signposted using the heading that we see immediately above this paragraph.

Season X

In modern Who, as in modern television at large, the basic unit of storytelling has shifted to the season (or series), as distinct from the story which can be seen to be one of the many differences with Classic Who, which itself differed from all over television shows in that the basic unit of storytelling was the story and not the episode. This is a particularly important development, as it underlines one of the basic needs and expectations of audiences who think nothing of bingeing their way through a boxset of DVDs or BluRays or an entire season or series of a show on streaming platforms. There then exists two dramatic ‘shapes’ that need to be observed at both the story and the season level; that is, not only is there a requirement for a stonking story told in a tight and compelling fashion using a three act structure, but there is also a similar requirement to the way in which a season or series builds its dramatic tension over the course of its run, which in this exercise of reimagination will usually be seven stories in total. We’ll talk more about exactly how this works when we get into each of the seasons, at which point this will also become clearer through its application, but look out for this as an important aspect of how we progress through this together.

Episode notes

Meanwhile, each episode will also have its own page, and will include general episode notes that outline the intent and scope of the reimagined story, as well as (and here’s the hard work lays) in a three-act breakdown of what that reimagined story could now look like.

Outside of the new Doctor and new Series, most posts will focus on one episode, not because I’m inadvertently contradicting myself that the series is the basic unit of narrative, but because I’m only human and focussing on one episode at a coupe of thousand words per post is probably the sanest possible option available if I’m to do this at all! (Let’s see how I go sticking to that…)

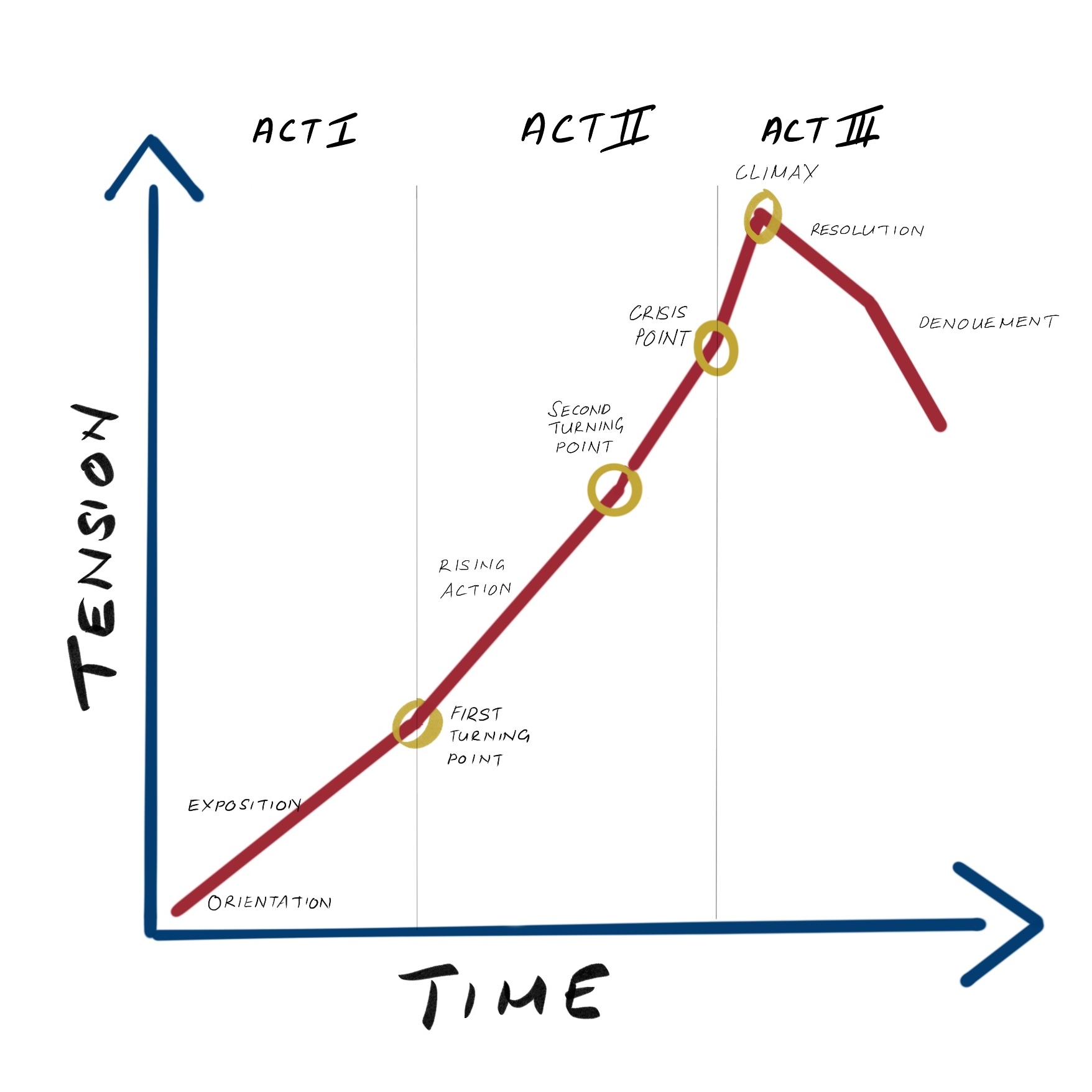

Each episode will largely be structured around an introductory statement of intent, and then the plot details that will be outlined following the three act structure most television has employed, literally for decades. It isn’t a science, but one way of breaking down the three act structure is as follows: Act One includes the Orientation, Exposition, and the First Turning Point; Act Two comprises the Rising Action, the Second Turning Point, and leads to the Crisis Point, while Act Three usually consists of the Climax, Resolution, and Denouement.

A key takeaway for me from Classic Who is how well this works in the very best scripts (and I mean ‘best’ from a technical, writerly point of view). Examples include stories like the first episode, “An Unearthly Child”, “The Ark in Space”, “The Horror of Fang Rock”, and “Ghostlight” amongst many others, where there is a tightness to the narrative – something that Paul Cornell likes to call the ‘shape’ of the narrative. Graphically depicted, a tight ‘shape’ conforms by and large to the three act structure and largely looks like this:

From New Who, the strongest lesson I have learned concerns ‘pacing’, or how quickly we proceed through these three acts. A great example is how the Orientation is usually placed entirely within the ‘cold open’; you know, that short bit at the very beginning of the episode and before the intro titles, such as in “The Unquiet Dead”, “Human Nature”, or “Mummy on the Orient Express”, where the central mystery of the episode is established via a ‘set piece’ that quickly and immediately hooks the audience and entices them to keep watching until the mystery or problem is resolved.

In terms of how the three act structure most commonly maps to a Doctor Who episode, I have come up with the following by-no-means-exhaustive ready-reckoner by way of what is hoped an illustration only:

Act One

Orientation

Obligatory TARDIS scene

and/or

A set piece that ‘hooks’ the audience with the secondary character/s who is an intended victim and/or likeable. Sometimes, this can turn out to be the villain.

Exposition

The Doctor and the companion/s arrive on the scene or are already in situ, and the Doctor soon deduces that something is wrong.

or

The Doctor and the companion/s arrive on the scene or are already in situ, and the Doctor has a secret reason for being there.

First turning Point

A surprise revelation concerning what is seemingly going on.

The villain is revealed to the Doctor and the companion/s and/or the secondary character/s and/or the audience.

Act Two

Rising Action

The Doctor and the companion/s and/or the secondary character/s work to uncover the mystery.

or

They work against the apparent plot of the villain after the Doctor deduces the villain’s intent.

Second turning point

The first confrontation between the villain and the Doctor, the companion/s and/or the secondary character/s.

The Doctor’s begins to formulate a counter-plan against the villain in a race against time.

or

The Doctor’s counter-plan begins to be enacted without the companion/s and the audience fully understanding.

Crisis point

The Doctor and/or the companion/s and/or the secondary character/s are in peril and/or the villain’s plans look about to be fulfilled. The Doctor is seemingly powerless and/or too late…

Act Three

Climax

The second and final confrontation of the Doctor et al and the villain. (Leads into à)

Resolution

The Doctor does something really clever and unexpected and saves the day, often exploiting the villain’s fatal flaw

or

The companion/s and/or the secondary character/s do something really clever and unexpected and saves the day, often exploiting their virtues.

Denouement

A beautiful moment that encapsulates the heart of Doctor Who and/or ties up the thematic strands, particularly as they relate to character/s’ growth. Provides the ‘moral of the story’.

If it hasn’t already become clear, I tend to think in structures, with the added ability of being able to zoom in on the minutiae and zoom out to see the structure as a whole and how each of its constituent parts relate to one another and fit together!

Oh, incidentally, by way of explanation regarding the use of the term ‘episode’ rather than ‘story’ or even ‘serial’, it is because the nature of the Netflix experience that I’m trying to prove that Doctor Who is, at this point in time, perfectly suited for provides that an episode can be as long as it needs to be to tell the story that is being told. There’s a much greater freedom to this than any lingering notion we might have of needing to have five instead of four episodes for The Daemons or insisting on 12 x 25 minutes for The Daleks’ Master Plan. At the same time, it does not preclude the idea that there are, effectively, ‘cliffhangers’ (something that I love from my childhood, especially when it is done right) that will break up the episodes into what are, in essence, separate acts (if not, on occasion, actual parts). There’s a greater flexibility that can be exercised with the telling the best possible version of each as a result, and that kind of flexibility is always a good thing.

Please share your thoughts in the comments section below

NEXT POST: THE FIRST DOCTOR

(Available 23 January 2023)